As you've probably seen, the writer David McCullough has died at age 89.

I mentioned his sonorous tones in Ken Burns's The Civil War a while back, but his books were good, too, an opinion that apparently I share with the Pulitzer Prize committee.

Mornings on Horseback and The Wright Brothers were good, although TBH I was more interested in the work of others who wrote about Dayton, Ohio's, other famous son, Paul Laurence Dunbar (a friend of the brothers). Americans in Paris was maybe too familiar to me in its subject matter to get a lot out of it.

But to get to the real stuff: writing inspiration.

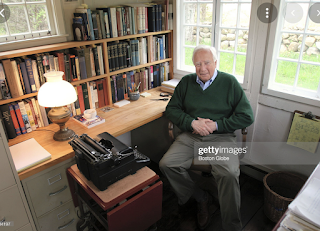

Working for much of his career in a tiny windowed shed behind his farmhouse in West Tisbury, Mass., on Martha’s Vineyard, Mr. McCullough tapped away on a manual 1940 Royal typewriter purchased for $25 in 1965.

“I like the tactile part of it,” he told the Times. “I like rolling the paper and pushing the lever at the end of the line. I like the bell that rings like an old train. … I even like crumpling up pages that don’t work. … I don’t like the idea that technology might fail me, and I don’t like the idea that the words are not really on anything.”

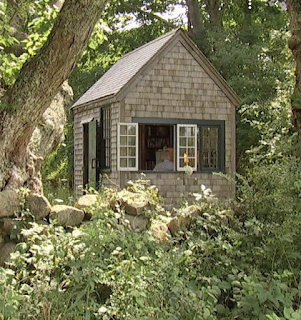

First, the writing house. It's behind his house on Martha's Vineyard, which--okay, we'll never see that kind of environment if we're not rich & famous, but we can envision the writing house.

From CBS, I learned its dimensions: 8' x 12'. This is slightly smaller than Thoreau's 10' x 15' cabin at Walden Pond, but McCullough wrote there rather than living there.

It's clearly a working space complete with file cabinets and an honest-to-god typewriter table. Those wings at the side of the table are for holding paper.

It's clearly a working space complete with file cabinets and an honest-to-god typewriter table. Those wings at the side of the table are for holding paper. Most important, a typewriter table is the best height for typing, 26" and not the 29" height of most of our desks, including the one on which I'm typing this. A typing table (if I had one) is a little low for typing on a keyboard, but when you're typing on a manual typewriter, that angle allows you to see better and also to press hard enough on the keys with a downward motion.

“People often ask me if I’m working on a book,” he continued. “That’s not how I feel. I feel like I work in a book. It’s like putting myself under a spell. And this spell, if you will, is so real to me that if I have to leave my work for a few days, I have to work myself back into the spell when I come back. It’s almost like hypnosis.”

“Writing history or biography, you must remember that nothing was ever on track,” Mr. McCullough told the Times in 1992. “Things could have gone any way at any point. As soon as you say ‘was,’ it seems to fix an event in the past. But nobody ever lived in the past, only in the present.

“The difference is that it was their present,” he continued. “They were just as alive and full of ambition, fear, hope, all the emotions of life. And just like us, they didn’t know how it would all turn out. The challenge is to get the reader beyond thinking that things had to be the way they turned out and to see the range of possibilities of how things could have been otherwise.”

P. S. Please forgive me for not commenting, WordPress bloggers. WP is on one of its periodic hate campaigns with me where it will not accept any identity or password, so I will have to make a new one.

No comments:

Post a Comment