-->

Apparently my reading for pleasure these days involves revisiting some of the twentieth-century writers, the

Mid-Century Males, that I read back as an undergraduate. J. D. Salinger is one; isn't he for everyone at that age?

Catcher in the Rye was okay, but in a short story class we read (and I reread many times)

Nine Stories, later discovering on my own, like just about every late adolescent everywhere,

Franny and Zooey, my favorite of his works.

Recently, I saw the Salinger documentary and checked out of the digital library Kenneth Slawenski's Salinger: A Life, Joanna Rakoff's My Salinger Year, and, because the other sources mentioned it, Joyce Maynard's At Home in the World. Apparently I was the last person on earth to have read Joyce Maynard years ago without knowing about The Salinger Connection, so I wasn't influenced by that when I read her.

Slawenski's book made much of Salinger's horrific WWII experiences, which started on D-Day and ended 299 days later after he helped to liberate concentration camps, something that the documentary emphasizes with a whole lot of (deservedly, I suppose) portentous music. Rakoff's My Salinger Year is delightful. It's a memoir of her year in the mid-1990s working at The Agency (Harold Ober and Associates) and handling both Salinger's fan mail and her employers' charmingly eccentric terror about encroaching technology. It's 1996, but the IBM Selectric is still king of the office.

Maynard's book is similar to the first two of hers that I read years ago (Baby Love, Looking Back).

She's a keen observer of her own life, but only of her own life, and

only of herself as the primary person within it. As she says many times in At Home in the World, she's not a reader, and she doesn't seem to be able to make those

connections except through pop culture, although she's very good at the

specifics of that. When she reports incidents like threatening to cut off her

long braided hair and her husband Steve saying, "It's your hair," the

implication is that he's too stolid and isn't paying sufficient attention to

her misery. Less sympathetic readers might think that she's being a drama queen. That doesn't prevent her from making

some good observations, though.

The whole Salinger thing that she was pilloried for is only a part

of the book, and apparently, in another interwebs development I totally missed, everyone is in a pro- or anti-Maynard camp: either "How dare you malign The Great Man?" or "How dare The Great Man have acted so cruelly toward women?" Maynard's take on the relationship, in the new preface, is not so

much "what was I thinking to quit Yale and move to New Hampshire with

Jerry Salinger?" as "how could he violate my innocence by

overpowering me with his adoration? Shouldn't we think of 18-year-olds as girls

instead of women?" It's a fair question, but really, who could have

stopped her or any of us at 18? That's not a hornet's nest I'm willing to wade into in this space.

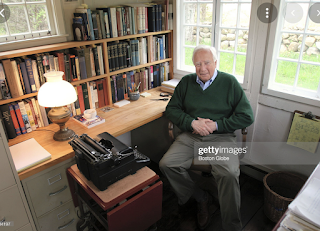

Salinger's writing advice--which is why I read the book--is actually sound. Salinger

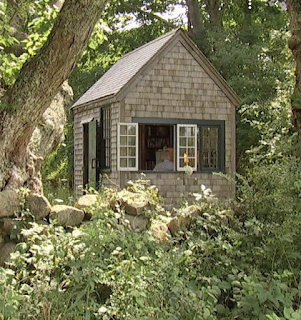

on writing: he writes every day, and by about 6.30 a.m. he's in his writing

room, later apparently the famous writing bunker where he would stay for weeks at a time. He shows Maynard at least two

manuscripts but says that writing for publication is all just ego and being of

the world, which he condemns.

Given that Salinger seems to have had the biggest ego in the Western

Hemisphere, this is a little disingenuous, but all right. The documentary says that there are books lined up to be published in 2015 and beyond.

Here's the thing that struck me, wanting as I did the details of the writing life: Maynard and Salinger eat their breakfast of thawed frozen peas and then both of them go off to

their writing tasks. Maynard never

mentions that in the memoir; it only comes up in an interview in the past

couple of years. Two writers,

living in a house together: that's the portrait that the interview gives and

that she's trying to avoid. Yet elsewhere she describes her writing routine, and she's a remarkably disciplined and productive writer.

Instead, the memoir section about her life with Salinger is all about making herself small, about

buying a sewing machine and cooking badly and leaving her stuff strewn around the

house and feeling wounded and above all not writing the memoir she's been

contracted to write. It's clear that she did feel diminished by his treatment, as who wouldn't? Yet by the

end of the year, the memoir has magically been written, with an epilogue heavily

influenced and partly written by Salinger himself because she wasn't being specific

and honest enough about what she was writing.

That's

the frustrating part of this memoir: it has the wrong focus, or maybe the right focus for Maynard but the wrong focus for someone who wants to read about writing. Even though the

focus of any Maynard book is always going to be Maynard, front and center, she

zeroes in on her father's alcoholism and her mother's weird obsession with her

as defining, formative moments. No

doubt they were, but this makes the whole thing come off as another of

innumerable recovery/abuse memoirs. She has had the experiences, though, and the talent to make more of the memoir than this.

What

I wanted to see more of was the narrative that's trying to emerge here and

can't, of Salinger trying to teach her something about writing and the approach that writers have to take to make it mean something. It has to be honest and something

you care about, he tells her; there's no glory in taking pot shots and writing snark about

beauty contests and Pillsbury Bake-Offs, although she does. Salinger warns her about this and about

adopting her mother's voice as she has adopted her mother's methods of applying

to contests, pitching stories, etc.

When she shows up at Salinger's door in

1997--which I think took a lot of courage, by the way--he tells her that she

had the capacity to become something but has become nothing, or something like

that. She's obviously made something of herself, having had a successful career, and she is a survivor, but is there anything in what Salinger says? Or is this just another case of a powerful man falling in love with an image that he creates and trying to destroy the image when she turns out to have a voice of her own?